Most Rev. Thomas L. Connolly

Godfather of Confederation

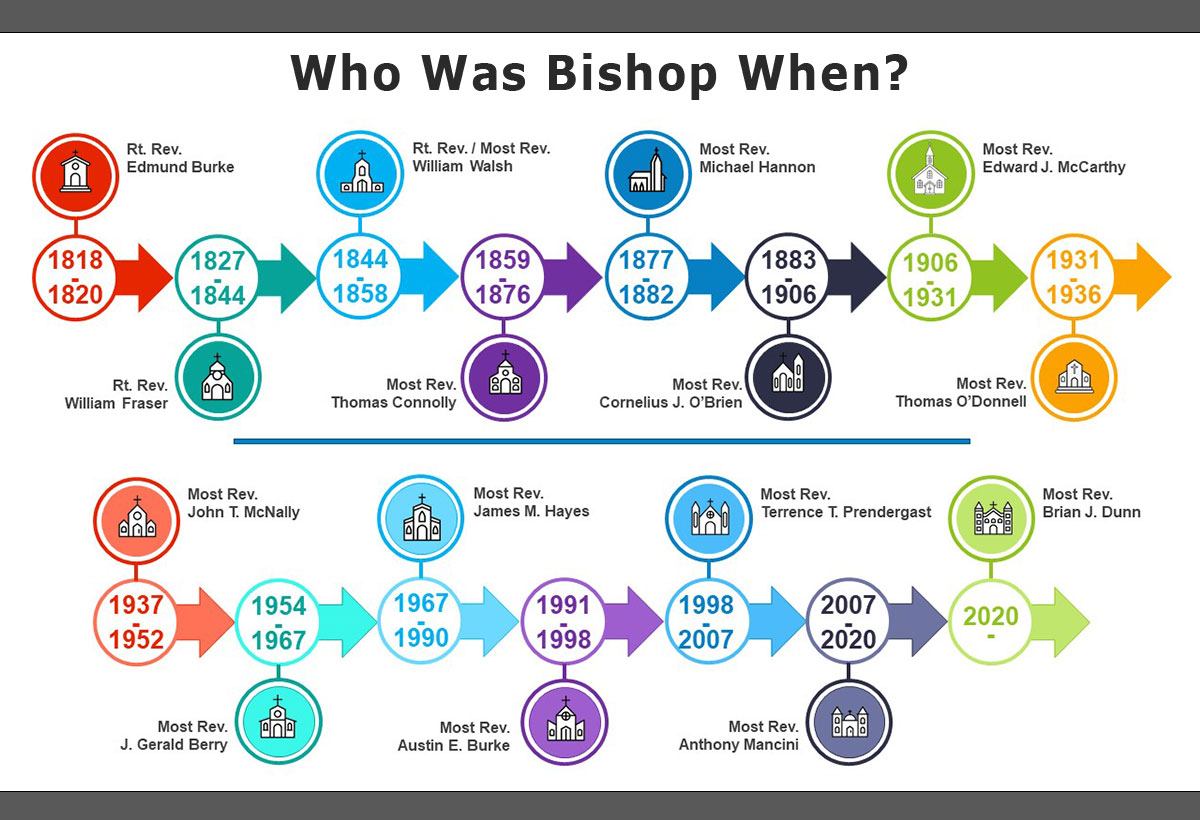

1859-1876

Archbishop Thomas Louis Connolly (1814-1882) has been described as the “Godfather of Confederation.” This title is warranted for his outsized influence in the passing of the British North America Act. It also, perhaps, suggests that he was a fervent nationalist. An Irish Catholic emigre of the first order, Connolly acted principally to benefit his own people: Maritime Irish Catholics. He should above all be commemorated as the man who stabilized their precarious position.

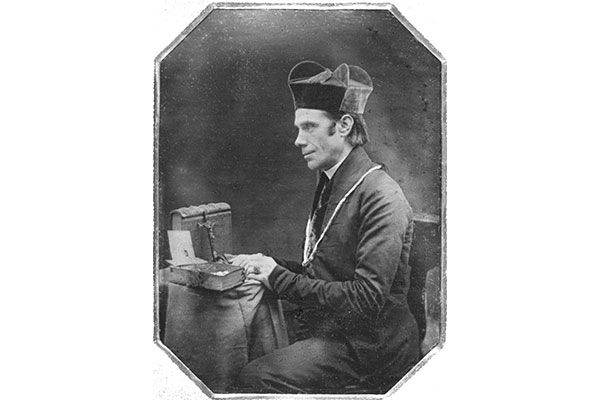

Connolly was born to an innkeeper in Cork, Ireland. He joined the Capuchin Order at age seventeen; the first act in a lifelong commitment to his faith. By age eighteen he’d undergone his studies in Rome, by age twenty-four ordination.

Connolly was born to an innkeeper in Cork, Ireland. He joined the Capuchin Order at age seventeen; the first act in a lifelong commitment to his faith. By age eighteen he’d undergone his studies in Rome, by age twenty-four ordination.

The twenty-eight year old priest accompanied William Walsh to Nova Scotia in 1842. The fellow Irishman had been appointed coadjutor bishop to the diocese of Halifax, and Connolly was to serve as his secretary. Walsh did not choose Connolly at random. The now experienced cleric had already distinguished himself through service at both Dublin’s Capuchin Mission House and as Chaplain in a penitentiary. Upon landing in Nova Scotia, Walsh elevated Connolly to the position of Parish Priest and, three years later, made him Vicar General. His impressive resume only expanded. By age thirty-seven, he’d been handed to keys to the Diocese of Saint-John.

It was in Saint-John that Connolly’s capabilities were tested. A cholera epidemic swept through the city. 1500 of its 30,000 residents perished in the span of a single summer, and mismanagement by local authorities left citizens frustrated and hopeless. Connolly administered last rites to those who had been “abandoned by all.” Come autumn, the number of newly made Catholic orphans had reached a sobering peak. Connolly took charge of their wellbeing, citing his role as “father of the flock.” An orphanage was established to house these children and nearly £1000 was gathered for their well being through the Bishop’s tireless campaigning.

It was in these years that Connolly began to develop a sober understanding of the Catholic situation in North America. As Bishop of Saint John, he made frequent excursions into the Protestant stronghold of American New England. Writing later in the 1860s, Connolly described the society there as one containing “more bigotry and more contempt of anything Irish” than anywhere he’d been before. Being a religious minority in a British colony was already a precarious existence. It could, Connolly concluded from these experiences, become much worse.

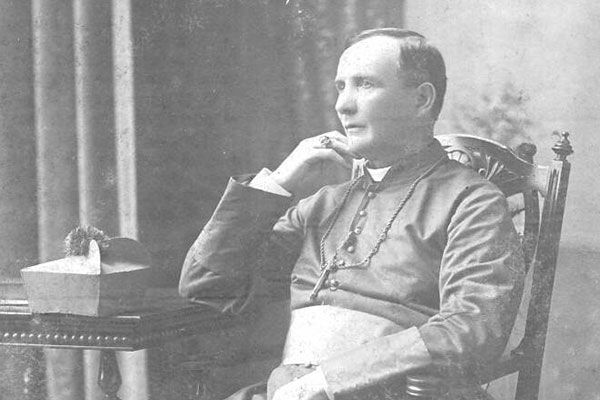

In 1859, Connolly’s successes in New Brunswick were recognized. He was named Walsh’s successor as Archbishop of Halifax upon the latter’s passing. It was in this role and throughout the 1860s that Connolly became an advocate for two deeply entwined issues. The first was a fight to acquire a separate Halifax Catholic school board. The second was Canadian confederation. His struggle with both would cement his reputation as a titan of Nova Scotian history.

Connolly’s unease over the precarity of Maritime Catholics fed his approach to these challenges. A separate school board was necessary, he and many of his Bishops argued, to protect catholics from being swallowed up in a protestant-dominated public education stream. Confederation was more complicated. For one, radical Irish militias – Fenians – had begun to foray into British North America from across the United States border. Connolly believed that “senseless” Fenian violence would only rally Protestants against Catholics. Worse still, many reasoned that an expansion-hungry US was likely to follow the example of these filibustering rebels. Uniting the provinces of Upper and Lower Canada, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick would guarantee British military protection against cross-border threats. Rallying for such a Union would demonstrate that Maritime Catholics rejected the Fenian cause.

The Archbishop became known for his hands-on approach to navigating these issues. He corresponded with early confederation advocate D’Arcy McGee, petitioned his parishioners to vote for a pro-union ticket, and wrote open letters to Halifax newspapers. He eventually became involved in delegations that aimed to convince colonial superiors that a Union was necessary. Writing to the Colonial Secretary himself, Connolly composed a rebuttal to anti-union magnate Joseph Howe, refuting all of the latter’s arguments against a united Canada. John A. Macdonald praised Connolly for this action, asserting that he was an important ally for their cause.

A compromise on schooling was eventually struck. The secular system would remain, but certain schools were allowed to be run by an entirely catholic faculty. Confederation, too, was achieved. Connolly was in London on March 29, 1867, and witnessed the signing of the British North America Act and birth of Canada.

Connolly has also been described as a man of “peace” who “built more bridges than he dug trenches.” This, too, mischaracterizes his nature. The Archbishop was anything but a pacifist, and knew when force or threats of force were necessary. Engaged in a rhetorical battle with Howe, Connolly cautioned the politician that “I will consent to anything but to become a Yankee, and that and all things leading to this I will resist to the death.”  What distinguished him was his ability to know when violence was pointless or detrimental, as was the case with his views on Fenianism. When interviewed about protestant Orange parades,Connolly expressed frustration and agreed that the aim of these demonstrations was only to make Catholics “kiss the rod that is held out for their castigation.” While he recognized that it would be their “duty” to resist in other circumstances, the present power imbalance made this unwise. Any revolt, he argued, would devolve into aimless mob violence that would cheapen Catholic morals and worsen protestant attitudes towards catholics. The most practical path forwards, he argued, was to turn the other cheek.

What distinguished him was his ability to know when violence was pointless or detrimental, as was the case with his views on Fenianism. When interviewed about protestant Orange parades,Connolly expressed frustration and agreed that the aim of these demonstrations was only to make Catholics “kiss the rod that is held out for their castigation.” While he recognized that it would be their “duty” to resist in other circumstances, the present power imbalance made this unwise. Any revolt, he argued, would devolve into aimless mob violence that would cheapen Catholic morals and worsen protestant attitudes towards catholics. The most practical path forwards, he argued, was to turn the other cheek.

Connolly’s life in the publiceye was long. In the 1870s, he participated as part of the foreigncontingent in the First Vatican Council. Already acquainted with Pius IX, Connolly spoke loudly and frequently against the doctrine of papal infallibility. The motion was supported by nearly every representative present, and Connolly claimed that he only went against the grain reluctantly. The Archbishop recalled how he had tried hard to side with the majority, but believed there was no historical precedent to support the doctrine. It was his duty, he concluded, to oppose it. The motion was carried through and, with characteristic grace in defeat, Connolly protested no more. He returned to Halifax and lived out his final years there. The finishing touches of Saint Mary’s Cathedral were completed in 1876, the year of his passing.

Bibliography:

Bilson, Geoffrey. “The Cholera Epidemic in Saint John, N.B., 1854,” Acadiensis, Volume 4, No. 1 (1974): 85–99.

Flemming, David B. “CONNOLLY, THOMAS LOUIS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed July 27, 2023, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/connolly_thomas_louis_10E.ht

Hanington, Jeffrey Brian. Every Popish Person. Archdiocese of Halifax, 1984.

The Thomas Louis Connolly fonds, Archdiocese of Halifax-Yarmouth Archives.

The photograph collection, Archdiocese of Halifax-Yarmouth Archives.

Photo collection, Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

Bridgeman Images.

Archives Contact

Sharon Riel

Archivist - Halifax Office

Archdiocese of Halifax - Yarmouth

(902) 429-9800 ext 314