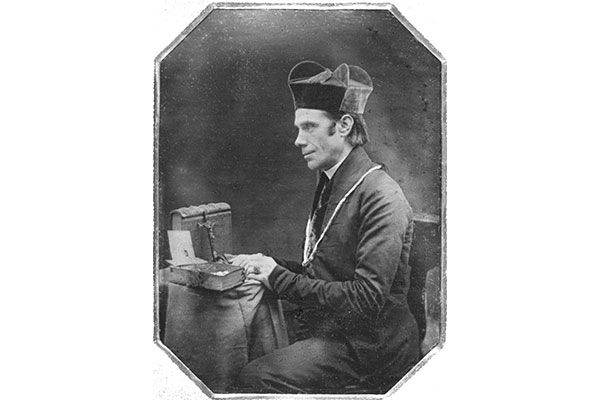

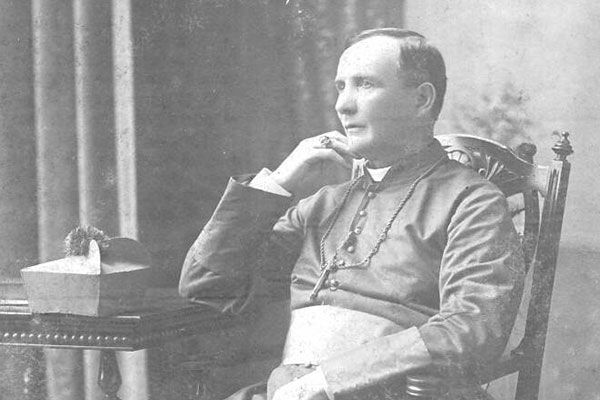

Most Rev. Michael Hannan

5th Archbishop of Halifax

1876-1882

During his eulogy for Archbishop Michael Hannan (1814 - 1882) Bishop McDonald asserted that the former’s journey mirrored those “sainted apostles” from Ireland. Like these sanctified heroes of old, claimed McDonald, Hannan had set forth from his home to advance Catholicism on foreign shores. One Father Wissel, who also spoke at Hannan’s funeral, described the late Archbishop as a “missionary to this lesser part of the world.”

Hannan’s life – which played out in Kilmallock, Ireland, until his  immigration to Nova Scotia at the age of nineteen –was one centred around this notion of being a missionary, of advancing the Church where it was beset on all sides. Hannan arrived in the Diocese at a time when Nova Scotia was, in the eyes of European colonial powers and the Roman Church, a frontier. The aim of the clergy in these early nineteenth century decades was simple: to solidify a Catholic presence within a colony controlled by a protestant empire.

immigration to Nova Scotia at the age of nineteen –was one centred around this notion of being a missionary, of advancing the Church where it was beset on all sides. Hannan arrived in the Diocese at a time when Nova Scotia was, in the eyes of European colonial powers and the Roman Church, a frontier. The aim of the clergy in these early nineteenth century decades was simple: to solidify a Catholic presence within a colony controlled by a protestant empire.

With this in mind, Hannan committed himself to the advancement of Catholic education – a cause that would occupy the majority of his professional career. Having already undertaken extensive schooling in Ireland, Hannan pursued his Doctorate of Divinity at Saint Mary’s College. He taught Latin and Greek to his classmates while he completed his studies.

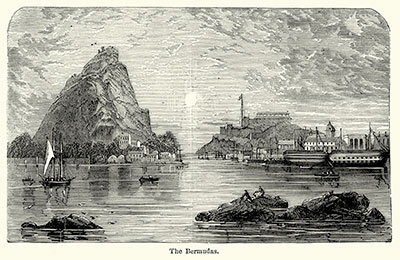

In 1847, Hannan served nine months as Priest of Bermuda – then an island colony technically underthe episcopal jurisdiction of the Halifax Diocese. Long neglected by Halifax bishops on account of its far-flung location and a lack of available resources, Hannan was the first Resident Priest to service the island’s small Catholic population. Though Hannan’s stay was brief, he laid the groundwork for a continued relationship between Bermuda and its host diocese. From the 1840s onwards, Bermuda was never without a resident priest. It grew to separate as its own diocese a century later.

Returning to Halifax from Bermuda, Hannan served on the city’s Board of School Commissioners and joined the fight to acquire denominational Catholic schools. This battle would be waged by Archbishops Walsh and then Connolly during the 1840s-60s – culminating with a deal that allowed certain public schools to be run by entirely catholic faculties. Premier Charles Tupper at times preferred to deal with Hannan over Connolly – favouring the former’s muted demeanour over that of his hotblooded countryman.

Returning to Halifax from Bermuda, Hannan served on the city’s Board of School Commissioners and joined the fight to acquire denominational Catholic schools. This battle would be waged by Archbishops Walsh and then Connolly during the 1840s-60s – culminating with a deal that allowed certain public schools to be run by entirely catholic faculties. Premier Charles Tupper at times preferred to deal with Hannan over Connolly – favouring the former’s muted demeanour over that of his hotblooded countryman.

It is here that cracks in Hannan’s supposedly upstanding character became evident. He kept back-channel communications open with Tupper for years to come, and frequently acted in the political realm on behalf of Catholics without Connolly’s knowledge or permission.

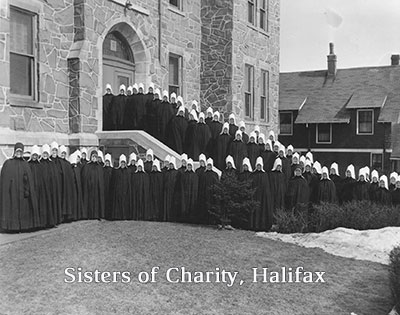

During his time on the Board of School Commissioners, Hannan also served as the Archdiocese’ Vicar General, and was Rector of Saint Mary’s Cathedral – a position he inherited from Connolly upon the latter’s consecration. It was in this cathedral that Hannan, acting as official escort, welcomed the Sisters of Charity to Halifax in 1849. It was the beginning of a relationship that would colour Hannan’s reputation for the rest of his days.

The Sisters of Charity, a religious congregation based in NewYork, had been summoned to Halifax atthe request of Walsh. They were to act as reinforcements in the quest to provide Catholic education to the community’s poor youth. In correspondence sent during his reign as Archbishop, Hannan described the Sisters of Charity as an order that had lost its “spirit of religion.” As dedicated to the cause of Catholic schooling as he was, Hannan’s enthusiasm for educators did not extend to the order. He described the order as having been “demoralized” by vanity and “contaminated” through what he viewed as improper fraternization with the laity.

NewYork, had been summoned to Halifax atthe request of Walsh. They were to act as reinforcements in the quest to provide Catholic education to the community’s poor youth. In correspondence sent during his reign as Archbishop, Hannan described the Sisters of Charity as an order that had lost its “spirit of religion.” As dedicated to the cause of Catholic schooling as he was, Hannan’s enthusiasm for educators did not extend to the order. He described the order as having been “demoralized” by vanity and “contaminated” through what he viewed as improper fraternization with the laity.

Hannan launched a rhetorical campaign against the Sisters of Charity and complained that Connolly showed unabashed favouritism towards them. He went as far as to imply that the relationship between Connolly and one particular member of the Order had become far too personal to suit either office. The Congregation was, Hannan noted, supposed to act independent of archiepiscopal influence.

Hannan’s principle complaint about the Order had little to do with their conduct or educational philosophy. As Superior General, he was technically its immediate supervisor. However, as was custom within the Order’s long standing hierarchical structure, its members owed equal allegiance to their Mother Superior. According to Hannan, such an arrangement was a violation of the established Church hierarchy, and had never been approved by Rome. The Sisters of Charity, for their part, argued that no transgressions had been made. This, he claimed, was evidence of the Order’s “spirit of rebellion.” Eventually, Hannan’s hostility cost him his role as Superior General and his seat on the Board of School Commissioners. Both disciplinary acts were enforced by Connolly.

All of this happened despite the Sisters of Charity and Hannan ostensibly sharing the exact same mission: to “advance the cause of religion in Halifax.” Indeed, the Order – which regularly conducted missions into the province’s rural parishes – would later complain that under Hannan, virtually none of the Archdiocese’ $45,000 annual budget was reserved for missionary work. Hannan himself pulled all funding from the Congregation-administered Saint Joseph’s Orphanage – despite it being the only Catholic-run institution that administered to Halifax’s poor youth. At one point in 1880, Hannan allegedly attempted to replace all teachers within the order with secular instructors.

Here, again, Hannan’s internal contradictions become evident. This was a man who devoted his entire professional and spiritual life to expanding the Catholic Church through education. He was also someone willing to jeopardise this mission over minor disagreements and challenges to his authority.

The conflict only escalated as Hannan gained more influence. He became Archbishop following Connolly’s death in 1876, whereupon he instructed loyal clergy members not to administer the sacrament to certain members of the order in their own residences. One priest – Father D’Homme – allegedly threatened to burn their personal residences down. Another informed a sister that he had been “instructed by the Archbishop” not to absolve her in her own home.

Hannan’s war was bitter and short. It was put to an end by Pope Leo XIII himself, who intervened on behalf of the order following several complaints by its members. The order was lifted from Hannan’s jurisdiction and placed under direct papal control.

Hannan died some months later in 1882. The Sisters of Charity endured. In a profound demonstration of forgiveness, the order did not detail any of Hannan's misdeeds in its official history. The period of 1876-1882 is instead described as a time of "misunderstanding" during which Hannan happened to be Archbishop. He is praised for offering last rites to a sailor condemned to hang.

Hannan embarked on oceanic voyages, endured conditions of hardship, and navigated the world of secular politics to grow Catholicism’s New World roots. But the Archbishop’s inability to handle authority prevented him from continuing this mission during his episcopal reign.

Bibliography:

Hanington, Jeffrey Brian. Every Popish Person. Halifax: Archdiocese of Halifax, 1984.

McCarthy, John M. Bermuda’s Priests. Quebec: P. Larose, 1954

The Michael Hannan fonds, Archdiocese of Halifax-Yarmouth Archives.

The photograph collection, Archdiocese of Halifax-Yarmouth Archives.

The photograph collection, Diocese of Hamilton in Bermuda Archives.

Photo archives, Mount Saint Vincent University.

Powers, Sister Maura. The Sisters of Charity Halifax. Toronto: The Ryerson Press, 1956

Roberts, Charles, and Arthur Tunnel, A Standard Dictionary of Canadian Biography: The Canadian Who Was Who. Vol. II.1875 -1933. Toronto: Trans Canada Press, 1934. 193-194

Archives Contact

Sharon Riel

Archivist - Halifax Office

Archdiocese of Halifax - Yarmouth

(902) 429-9800 ext 314