The National Day of Prayer in Solidarity with Indigenous Peoples is celebrated on December 12 every year, on the feast day of Our Lady of Guadalupe. This day was started by the Canadian Indigenous Council, a part of the Conference of Catholic Bishops, in 2002.

On this day the Canadian faithful are called to pray in solidarity with the Indigenous of this land as we continue our journey of healing and reconciliation. Resources for prayer and reflection can be found at www.cccb.ca or Our Lady of Guadalupe Circle. OLGC is a Catholic coalition of Indigenous people, bishops, clergy, lay movements and institutes of consecrated life, engaged in renewing and fostering relationships between the Catholic Church and Indigenous Peoples in Canada.

Find out more about ...

In 1610 after observing and interacting with French missionaries, Grand Chief Membertou decided to become a Christian Catholic. He was baptized by Fr. Jesse Fleche, SJ in February of that year. This essentially meant that the whole Mi’kmaq nation became Catholic. Chief Membertou’s Grand Council advised him to seek a binding accord between the Mi’kmaq nation and the Holy See – a treaty of friendship and peace. This 1610 concordat, agreement between the Vatican and the Mi’kmaq nation, established three things: an equal partnership between the indigenous and the Vatican, acknowledgement of the hospitality extended by the Mi’kmaq to the French missionaries, and an ability for the Mi’kmaq to practice the Catholic faith, including celebrate Mass, in their own language. This last point is of particular note. It was not until the 20th century that other Catholics around the world could celebrate Mass in the local language of the people.

The Mi’kmaq were Influenced by and lived in community with French missionaries and settlers for many years. During those years the Mi’kmaq in Nova Scotia practiced the Catholic faith incorporating Mi’kmaq spirituality in their practice of the faith.

Some key moments in our more recent history:

- 1917 - Sacred Heart Mission Church is established on Millbrook First Nation.

- 1930 – Government opens the Shubenacadie Indian Residential School and is administered by the Archdiocese of Halifax.

- 1948 - St. Catherine Parish is established on Sipekneꞌkatik First Nation (Indianbrook); renamed St. Kateri Tekakwitha Parish in 2012.

- 1956 – Oblates of Mary Immaculate take over administration of the residential school from the Archdiocese.

- 1967 – Shubencadie School closes.

- 1986 – Grand Chief Donald Marshall establishes October 1 as Treaty Day in Nova Scotia.

- 1988 – Saint Mary’s Cathedral Basilica hosts first Treaty Day Mass; this continues to present day.

- 1992 and 1993 – The late Archbishop Austin Burke met with the Mi’kmaq people in Sipekneꞌkatik First Nation and Millbrook First Nation to celebrate a Mass with them and apologize for the Church’s part in Shubenacadie Indian Residential School.

- 2011 - Representatives from the Archdiocese, including Archbishop Emeritus Mancini, take part in the Truth and Reconciliation Hearings in Halifax.

- 2018 – Archbishop Emeritus Mancini and Bishop Dunn, then bishop of the Diocese of Antigonish, meet with Mi’kmaq representatives in a series of Listening Circles with the aim of listening to hear the experience of the Mi’kmaq and what is wanted and needed as pastoral support to the community.

- 2018 – At the October 1 Treaty Day Mass, Archbishop Mancini and Bishop Dunn (then bishop of the Diocese of Antigonish) kneel before the Mi’kmaq chief and people present to express their sorrow and apology for the wrongs done by the Church at Shubenacadie Indian Residential School and ask for their forgiveness.

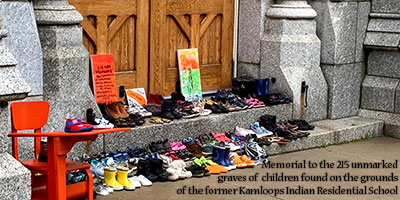

- 2021 – Archbishop Dunn offers a Sunday Mass for the repose of the souls of the 215 children found on the former grounds of Kamloops Indian Residential School. During his homily he shares his reflections on residential schools and offers his apology and support to the Mi'kmaq.

The residential school system is a dark mark in the history of Canada and the Church. It is important to listen to the experiences of residential school survivors. As Catholics, and Canadians, we must acknowledge the hurt and trauma caused, apologize for the wrong doing, and take the necessary steps to work together – indigenous and non-indeginous - to find a path that leads to healing and reconciliation.

Shubenacadie Residential School

Open from 1930 to 1967, Shubenacadie Residential School was the only residential school in the Maritimes. It functioned within the residential school system put in place by the government and administered by churches and religious organizations. The aim of the school was to assimilate Indigenous children as part of a nationwide effort to suppress Indigenous culture, identity, and history. When it opened the school was administered first by the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Halifax and later the Missionary Oblates of Marie Immaculate and staffed by the Sisters of Charity of Halifax.

Mi’kmaw and Wolastoqkew children from Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick, and Quebec attended Shubenacadie Indian Residential School. There are many horrific stories of students experiences that included harsh discipline; malnutrition and starvation; poor healthcare; physical, emotional, and sexual abuse; medical experimentation; neglect; the deliberate suppression of their cultures and languages; and loss of life. While touted as a place of education we now know it was far from that.

The Shubenacadie Indian Residential School was built in 1928-29 in the Sipekni’katik district of Mi’kma’ki, at the top of a small hill between Highway 2 and the Shubenacadie River overlooking the village of Shubenacadie. It is seven kilometers from Sipekne’katik First Nation. The abandoned school building was demolished in 1986 after a fire burnt most of the building. A plastics factory now stands where the school used to be.

In 2020 the site was designated a National Historic Site by Parks Canada. There are plans for a commemorative plaque to be placed at the site in the fall of 2021.

Residential Schools FAQs

The discovery of 215 unmarked graves of children found on the grounds of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School in May 2021 shone the light once again on the residential school system. At that time a list of Frequently Asked Questions was created and can be found by clicking here.

Treaty Day was established on October 1, 1986 by Grand Chief Donald Marshall Sr. This day commemorates the key role of treaties between the Nova Scotia Mi’kmaq and the Crown. The day specifically recalls the Treaty of 1752. The annual ceremony reaffirms the historic presence of the Mi’kmaq who have occupied the land for thousands of years who sought to find friendship and peace with the early settlers. The Mi’kmaq Nation and the Crown exchange gifts to mark each October 1.

Treaty Day activities and events are a way for Mi’kmaq to gather and for non-indigenous people to learn more about Nova Scotia’s history. Each year Saint Mary’s Cathedral Basilica hosts a Treaty Day Mass as part of the festivities. At this celebration representatives of the Church, Mi’kmaq chiefs and people, and many others, come together in worship and prayer.

All are welcome to join in the Treaty Day Mass annually held on October 1 at 9:30am.

Throughout the life of the local Church in Nova Scotia, church leadership have prayed with, had conversations with, and offered pastoral support to the Mi’kmaq communities. In the early years of Nova Scotia’s beginnings, there are accounts of interactions with French missionaries, early Acadian settlers, Jesuits missionaries as well as others where faith was shared. In more recent times, some notable encounters include:

- In 1992 and 1993 the late Archbishop Austin Burke met with the Mi’kmaq people in Sipekneꞌkatik First Nation and Millbrook First Nation to celebrate a Mass with them and apologize for the Church’s part in Shubenacadie Indian Residential School.

Copies of his homilies can be found by clicking here.

- In 2010 a number of Bishops and other clergy took part in celebrations as part of a great powwow held to commemorate the 400th Anniversary of Grand Chief Henri Membertou’s baptism into the Catholic faith. This four - day gathering took place on the Halifax Commons.

- In 2011, Archbishop Mancini and other representatives from the Archdiocese of Halifax-Yarmouth took part in the Truth and Reconciliation Hearings in Halifax.

- In the spring of 2018, Archbishop Emeritus Mancini and Bishop Dunn, then bishop of the Diocese of Antigonish, met with Mi’kmaq representatives in a series of Listening Circles with the aim to listen to one another and find ways to work together to better the relationship between the Mi’kmaq and the local Church.

- In 2018, at the Treaty Day Mass on October 1, Archbishop Mancini and Bishop Dunn (then bishop of the Diocese of Antigonish) knelt before the Mi’kmaq chief and people present to ask for their forgiveness and express their sorrow and apology for the wrongs done by the Church at Shubenacadie Indian Residential School.

- In June of 2021 Archbishop Dunn offered a Sunday Mass for the repose of the souls of the 215 children found on the former grounds of Kamloops Indian Residential School. During his homily he shared his reflections on residential schools and offered his apology and support to the Mi'kmaq. The Archbishop spoke of what our Church has done in the recent past as well as what he hopes we can continue to do moving forward. The portion of Archbishop Dunn’s homily where he speaks of the residential schools can be watched here: www.youtube.com/watch?v=D_JZ_YDZXKghe or visit Video: halifaxyarmouth.org/video

Historical accounts from Catholic clergy and missionaries in the 18th century speak to the efforts representatives of the Church made to learn about the Mi’kmaq people and culture. Many missionaries also learned the Mi’kmaq language so that faith teaching and prayer could be better said and understood.

Finding a common language or common ground can be achieved by learning to listen better to one another - truly listen. Archbishop Dunn hopes to do just that – listen and learn from the Mi’kmaq. He has expressed his commitment to working with our local Mi’kmaq communities to seek a path that will lead us all towards a stronger relationship between the local Church and our indigenous communities.

Plans for more Listening Circles, educational opportunities for clergy and the faithful, and shared moments of prayer and worship such as Treaty Day are some of the small ways that the Archdiocese of Halifax-Yarmouth is creating spaces for sharing, storytelling, and faith. May we find more opportunities to better know and learn the stories and culture of our Mi’kmaq brothers and sisters.

Saint Kateri Tekakwitha and Saint Anne, pray for us!

Recent Letters to the Mi’kmaq

- Archbishop Dunn's Letter to Indigenous Leaders - June 2023

- CCCB pastoral letters to Indigenous People of Canada

Mi’kmaq Parishes in the Archdiocese of Halifax-Yarmouth

FAQ's

Residential Schools

Frequently Asked Questions

(June 2021)

Contact

(902) 429-9800

Resources:

- Reconciliation Fund Collection FAQs - from Archdiocese of Halifax-Yarmouth

- Residential Schools - FAQ's - from Archdiocese of Halifax-Yarmouth

- CCCB Indigenous Peoples Page – prayers, initiatives, and resources from the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops.

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission Reports

- Our Lady of Guadalupe Circle – a Catholic coalition of Indigenous people, bishops, clergy, laity and religious engaged in renewing and fostering relationships between the Catholic Church and Indigenous Peoples in Canada.

- Kwilmu’kw Maw-klusuaqn -Mi’kmaq Rights – an advocacy group that works to uphold Treaty rights.

- Residential Schools - FAQ's - from Archdiocese of Toronto: English (pdf) - French (pdf)